Chapter 15

Load-Packer 800 Series

For all of the engineering and investment that had been poured into the effort, Gar Wood T-series trucks didn't find many buyers in 1965 and 1966, and unitized construction refuse trucks failed to transform the industry. Buyers still favored the traditional separate body, mounted on the truck chassis of their choice. This included not only the popular "residential" or light-duty rear loaders, but also newer heavy-duty, high-compaction models such as the Leach 2-R Packmaster and Load-Master LM-100. Gar Wood acknowledged this reality with the 1967 introduction of the Load-Packer 800 series, a bulk rear-loader available as a separate body in 20 or 25-cubic yard sizes. The LP-800 filled the gap between the LP-700, which was still a formidable light-duty packer, and the massive T-series. While it is possible that the 800 may have been planned all along, it is more likely that it was a "stop-gap" design, engineered very quickly to avert total catastrophe in the wake of the T-series.

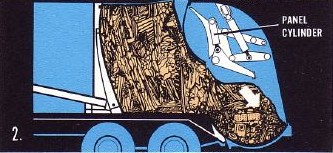

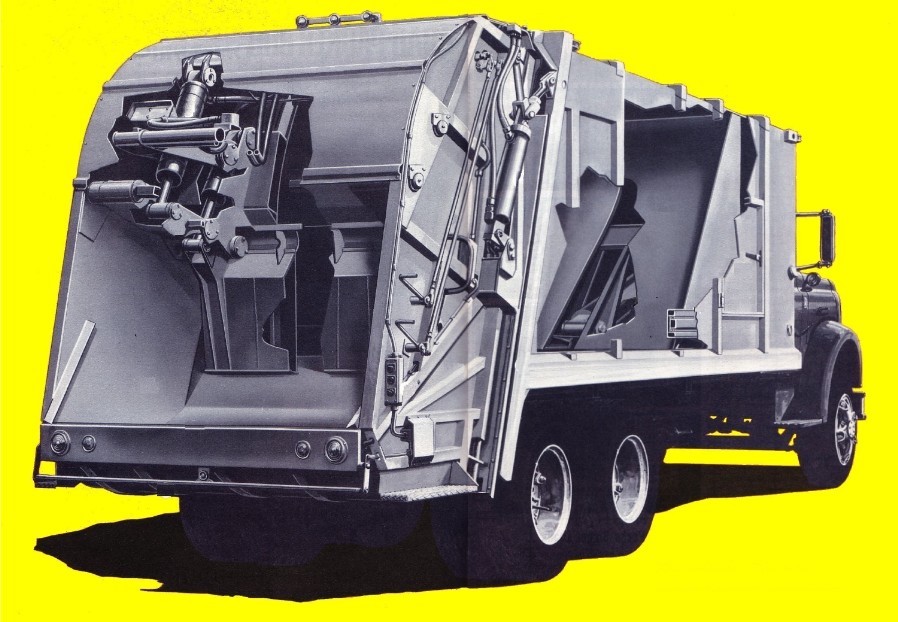

Even if the LP-800 was hurriedly engineered, it was a cleanly designed heavy-duty rear loader. Occupying a spot in the middle of the product line, it claimed compaction densities of up to 1,000 pounds per cubic yard. The packer unit borrowed heavily from the T-series, particularly the prototype TX-30 of 1964, though it was a refuse body only, and not a complete, unitized vehicle. A two-panel, swing link packer swept the 2-cubic yard hopper, with a more conventional lift-and-pack trajectory than that of the T-series. The upper panel was suspended on four links, which bore the brunt of compaction forces on their bearings. This eliminated tracks and slots in the hopper sides, which were prone to wear and clogging. This all-new swing link method greatly reduced friction losses inherent in track-and-roller systems, and thus transmitted more hydraulic force on the load itself. The lower links were actuated by hydraulic cylinders connected at the mid-point of the beam, giving a mechanical advantage that increased the actual packing force to a whopping 160,000 pounds. The upper links served to stabilize the upper panel as it moved within the hopper. Two more cylinders opened and closed the lower panel in the conventional manner, though it was guided inward during its descent by heavy bars welded to the hopper side walls.

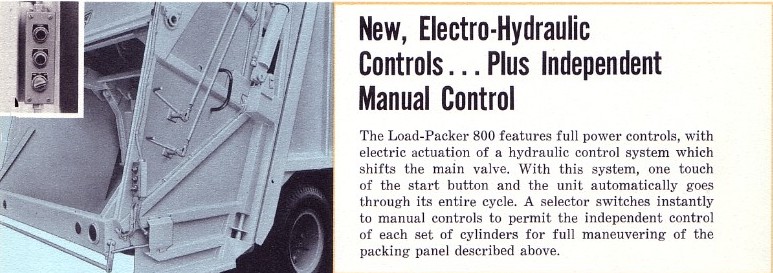

Carried over from the LP-700 was the Gar Wood Constant Density Compaction (CDC) system and curved ejector blade. The CDC system used a pressure sensing valve in the packer cylinder circuit to control ejector travel, rather than ejector relief valving. Coupled with the more powerful packer, the LP-800 delivered true high-compaction loads. The big 2-yard hopper accommodated lots of loose refuse, or bulky items like furniture appliances, which it could easily digest. Packer control was electro-hydraulic with push-buttons. The buttons on the control panel supplied DC current to solonoid-shifted hydraulic valves. This was a nod toward Heil, which had pioneered electric controls in 1960 with the Mark II Colectomatic.

The guide bars welded to the inside of the hopper sidewalls above the loading sill were a truly unusual feature of the 800. Their job was to mechanically assist the lower (sweep) panel to partially close as it descended towards the hopper sill. Because of the trajectory of the swinging upper panel, the lower panel would have been projecting past the loading sill at the bottom of the arc, and unable sweep inward during the next phase of the cycle. Using guide bars to mechanically close the panel alleviated the need for a complex hydraulic circuit to perform that function. However, it is curious that the designers didn't simply extend the length of the tailgate structure to accommodate the arc of the panel (as E-Z Pack did later with their Goliath), which would have resulted in an even larger hopper capacity. Perhaps Gar Wood engineers felt that by keeping the tailgate dimensions smaller, the shorter overall length would be better for maneuverability.

For a two-panel batch-loader, the LP-800 was fast: reload time was 7-seconds, and just 17-seconds for the entire cycle. To withstand the high stresses, the hopper floor and lower sidewalls were made from 3/16" heat-treated high-tensile steel, rated at 100,000 pounds yield. Another novel feature, which was borrowed from the T-series, was the Gar Wood exclusive auto-locking tailgate system. This simple mechanism utilized part of the stroke of the tailgate lift cylinders to operate the lock pins, which secured it to the body. It was an ingenious device that was practical and ahead of its time. The tried-and-true Load-Lift kick-bar container hoist was optional, as was an 8,000 pound overhead winch, capable of handling containers up to 10-cubic yards.

The LP-800 seems to have been a capable bulk packer. However, it was not without its share of problems as is recalled by Dana Gregory who lived in the metro Boston area during the 1960s. "The word I heard through the grapevine in the Boston area was that the electro-hydraulics were undependable. I know of one city adjacent to Boston who purchased two 25-yard 800 bodies on GMC cabover chassis. Nice, nice trucks. One worked great. The hydraulics were trouble-free, and it packed a huge load. The other was just the opposite: problems with the hydraulics caused the packer to cycle slower than normal, and ejection was also very slow. I saw this with my own eyes."

Gar Wood quickly adding manually operated rod-and-lever packer linkage to supplement the electric system on later models, which would tend to confirm that the electronic controls were problematic. There is also a report of the guide bars breaking off from the hopper, but it is unclear how widespread that problem was. All-in-all, the LP-800 appears to have been a good design that really packed superbly. It borrowed the best elements of the T-series rear loader, and left behind the worst. Had it arrived in 1965, and paired with the revamped LP-700, the future of Gar Wood Industries may have been entirely different. But by 1968, the role of the LP-800 was clearly to try and win back customers who had gone to Leach and Load-Master in the wake of the T-Series debacle. Ultimately, the 800 would be unable to save the one-time industry leader from the troubles yet to come.

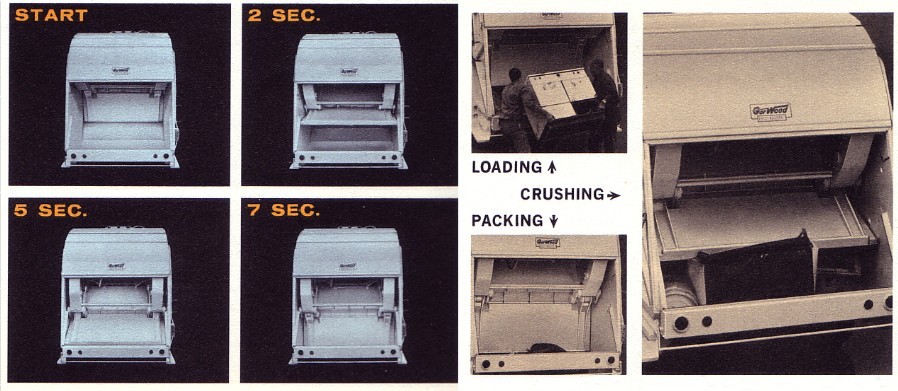

Loading position, with the 2-cubic yard hopper ready to receive material.

|

As cycle starts, lower panel opens back over the load.

|

Next, the packing cylinders extend, swinging the assembly downward. Guide bars welded to the hopper sides partially close the lower panel at the end of its descent.

|

Lower panel cylinders then extend, closing panel which sweeps and crushes refuse in the hopper.

|

During final stage, packing cylinders retract and pull the assembly upward. The leverage angle of the packing cylinders and lower linkage increases, multiplying packing force in increasing degrees until the end of the cycle. Upward motion of blade eliminates "column build up" within the body.

|

Cut-away view of a later-model LP-800; note the manual control levers on the right side, a feature added to supplement problematic push-button electric system of the earliest models.

|

The LP-800 could devour bulk items such as furniture and large appliances

Powerful new Load-Packer was best ever, delivering loads up to 1,000 pounds per cubic yard.

Going to work on a pile of furniture, this later-model 800 has electric and manual controls.

Detail of the dual control setup used on later models

Stylish LP-825 on International Harvester Fleetstar truck chassis

Crewmen from the Cleveland Division of Streets load an LP-820 on Ford C-series cabover.

July, 1970: Fleet of five LP-825's on Diamond REO chassis for Monroeville, Pennsylvania.

LP-820 trails an LP-600 and LP-700 going into a Cleveland incinerator

7/30/14

© 2014 Eric Voytko

All rights reserved

Photos from factory brochures/advertisements except as noted

Logos shown are the trademarks of respective manufacturers

|

| |