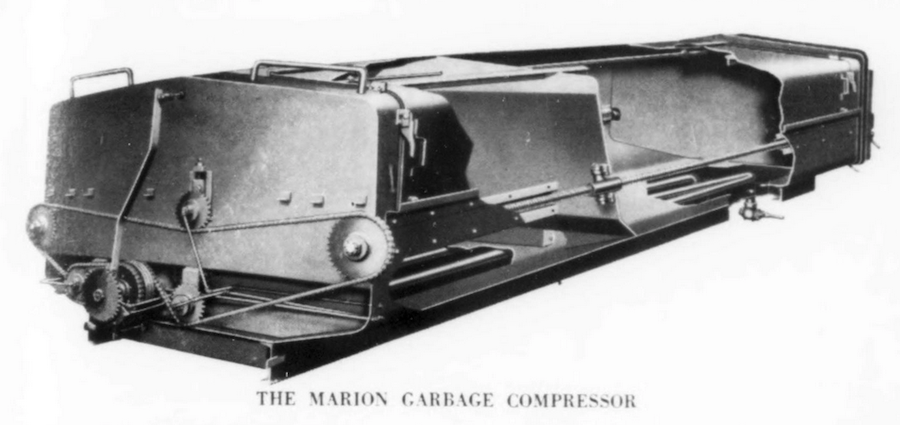

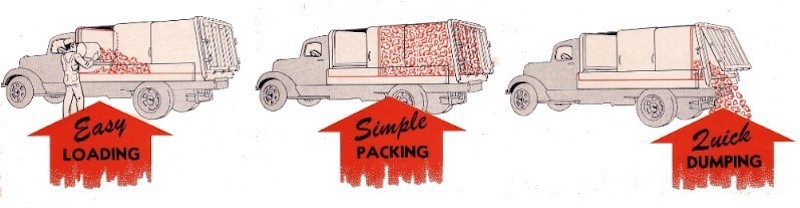

The Marion Steel Body Co. of Marion, Ohio, was an early manufacturer of hoists and dump bodies and even metal burial vaults. In 1934, Marion began producing the Refuse Compressor, a garbage body that was among the earliest mass-produced packers in America. The Compressor was a simple side-loading packer, of the type that would eventually become popular with numerous manufacturers following the Second World War. In 1935, the company name was changed to Marion Metal Products Co. to better identify with the diverse products the company made. Marion's concept blazed the trail, which was later followed by Pak-Mor, M-B, Packa-Van, and Galion (E-Z Pack), as well as front loader pioneers such as Bowles and Dempster. It consisted of an all-steel, enclosed body that contained a movable partition, sliding from front to rear, which compacted the load and served as an ejector panel for unloading. Though it marked a great leap forward in refuse body technology, the Marion Refuse Compressor was in way a variation of the established 'template' system, a method for unloading open refuse/garbage wagons, and later, motor trucks.

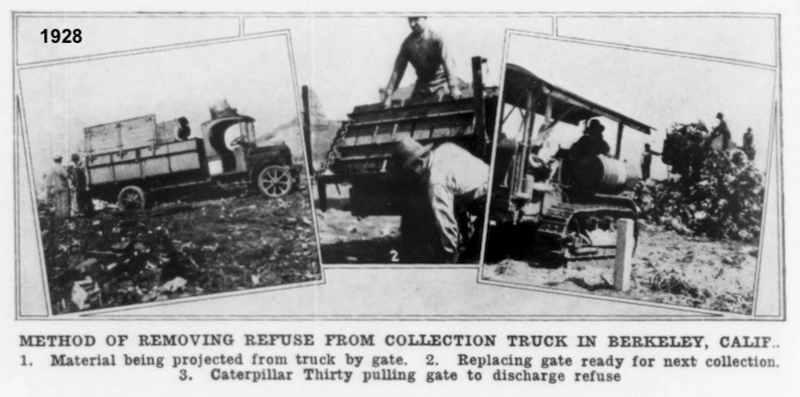

Templates allowed open-bodied collection trucks that were not equipped with hoists to quickly and easily discharge their contents at the dumpsite. A template was merely a partition (made of wood or metal) that was constructed to fit the general dimensions of the inside a truck body, and was stored upright at the extreme front end of the body. Ropes or chains were attached to template, and laid down on the bed floor or sides of the body, extending past the rear end. Material collected was deposited in the body behind the template and over top of the chains. When the filled truck arrived at the dump, the tailgate or end doors were opened, and the chains were connected to a tractor or another truck, which pulled the template rearward, clearing the truck body along the way. The template was then recovered from the discharged load, and replaced at the front of the empty body, ready for the next load. Alternately, the chains could be affixed to an immovable object, and the truck was simply driven forward to accomplish unloading.

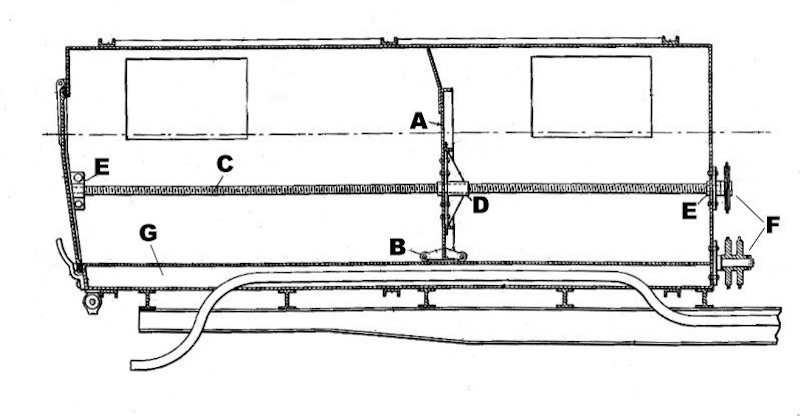

Refuse was loaded through large side doors, on to the body floor in front of the compressor plate. The plate reciprocated by way of twin rotating screws on either side, running the length of the body. The screws were threaded through phosphor-bronze nuts affixed to either side of the plate. When rotated, the screws, being threaded through the fixed nuts, caused the plate to move rearward in the body to compress (or eject) the material loaded within. By simply reversing the rotation of the screws, the plate was then drawn forward, ready for the next load. Power to operate the rotating screws came by way of a clutch and reversible gearbox between the cab and body, tapped directly from the vehicle drivetrain. Connecting between the final drive and screws was a series of chains and sprockets. Thus, the Marion Refuse Compressor may be categorized as a mechanical packer, and had no hydraulic system.

Early Marion advertising contrasted their modern packer body with the horse-drawn wagons then commonly used in collection fleets. Despite its name, Marion clearly had designed the body with garbage collection in mind, meaning putrescible kitchen food waste, which was typically picked up separately from combustible rubbish. In fact, the latter was not even collected by many municipalities, being the responsibility of the citizens to dispose of by incineration, scavengers or other means. Bodies were initially offered in six cubic yard capacity, with a 110-gallon liquid sump built into the body. The sump collected liquids squeezed out of the garbage loads, an important feature for cities where final disposal of garbage was to by incineration. Loading doors were typically at the front of the body, near the cab, but some models were built with front and rear openings. The Refuse Compressor was a landmark design in mechanized collection equipment, and established Marion as an early leader in the industry. However, the design may have been too advanced for its time. Undoubtedly, many cash-strapped cities could not justify the expense of these new-style packers during the Depression years. Their old open-type dump trucks were a far cheaper alternative, despite the obvious sanitary deficiencies. Additionally, pure garbage loads are inherently dense, and thus less effected by compression. Marion's product was better suited to collection of combustible rubbish or a mixed stream, but it lacked a suitable body capacity for that duty. Furthermore, demand for rubbish collection would not peak until after the Second World War. Marion would be ready with an improved model, once again ahead of the rest of the fledgling refuse body industry.

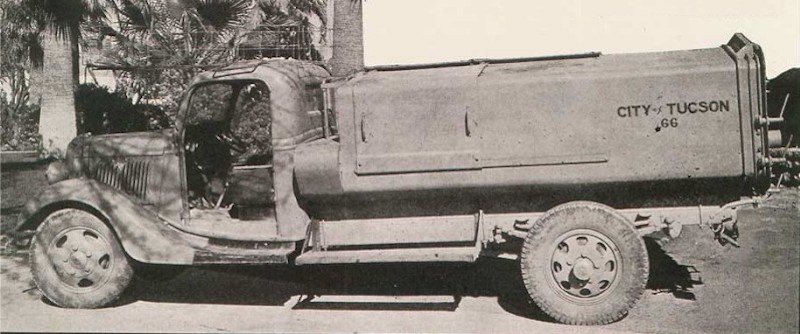

1936 Marion Refuse Compressor serving Tucson, Arizona Marion Hydropaka

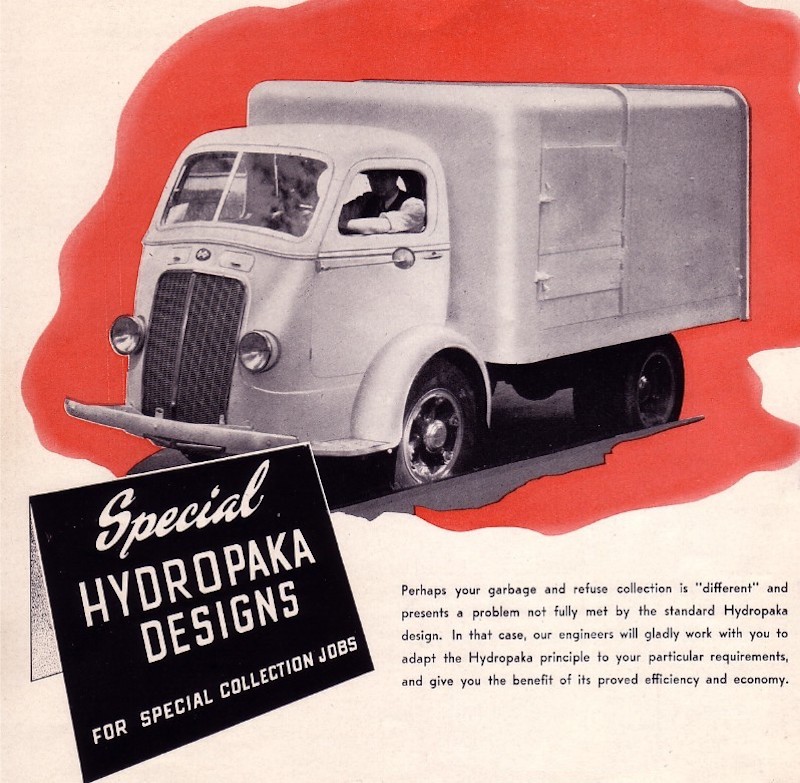

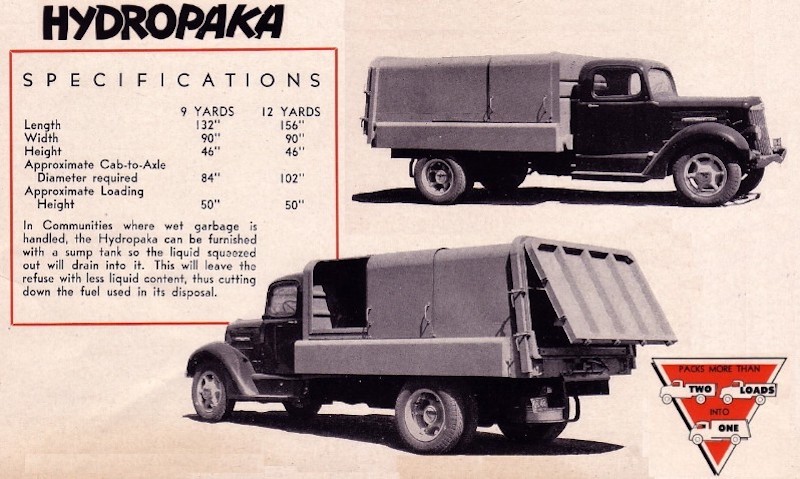

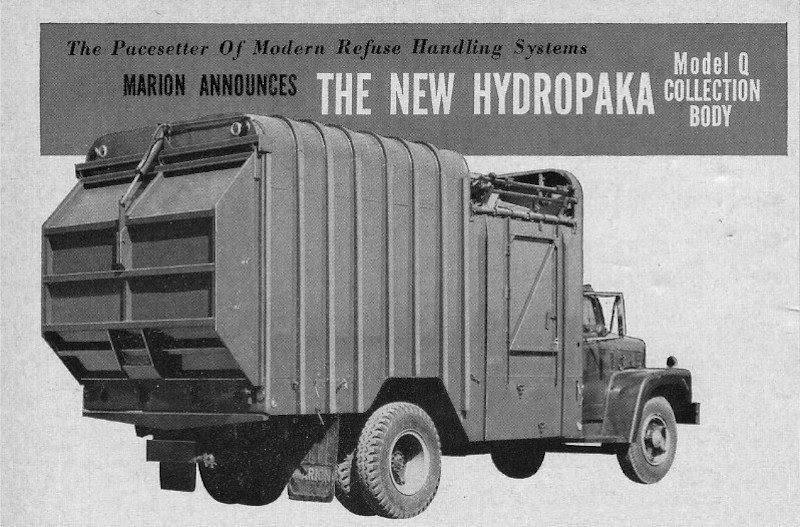

The new body was available in standard sizes of 9 or 12 cubic yards, capacities much better suited for collection of bulkier material. Even larger sizes could be had by special order. Hydropaka was on the market by 1945, and possibly as early as 1940-41, though the earlier date is subject to confirmation. In either case, it marks another advance in technology for Marion; an all-hydraulic side load packer, a full decade or more ahead of the 1955 E-Z Pack. The lack of body bracing on the Hydropaka would seem indicative of a somewhat mild hydraulic system, at least by modern standards. Claimed compression was a minimum 50:1 (their slogan being "Packs more than two loads into one"). The liquid sump, standard on the Compressor, was now optional. The Hydropaka would be Marion's main refuse body during the 1950s.

From an un-dated Marion brochure; truck is a 1940 International, and this Hydropaka body looks nearly identical to the Kompaka introduced by Municipal Sanitation Corporation the same year. The history of the Kompaka ends where that of the Marion Hydropaka begins.

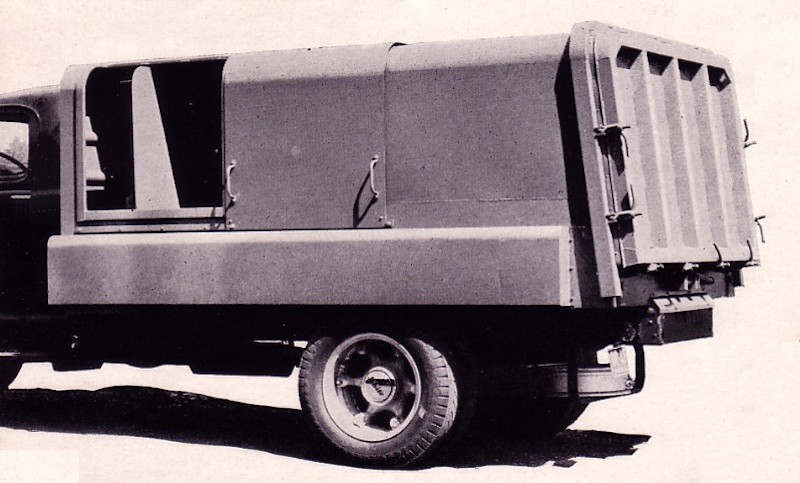

The more common version of the Hydropaka; side bulges in body may have housed hydraulic cylinders

Hydropaka bodies were substantially larger the the Compressor of the 1930s

Circa 1953 Hydropaka used by the City of Cleveland Hydropaka Model Q and Model S

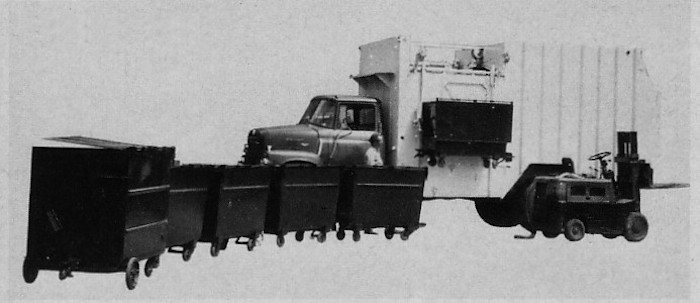

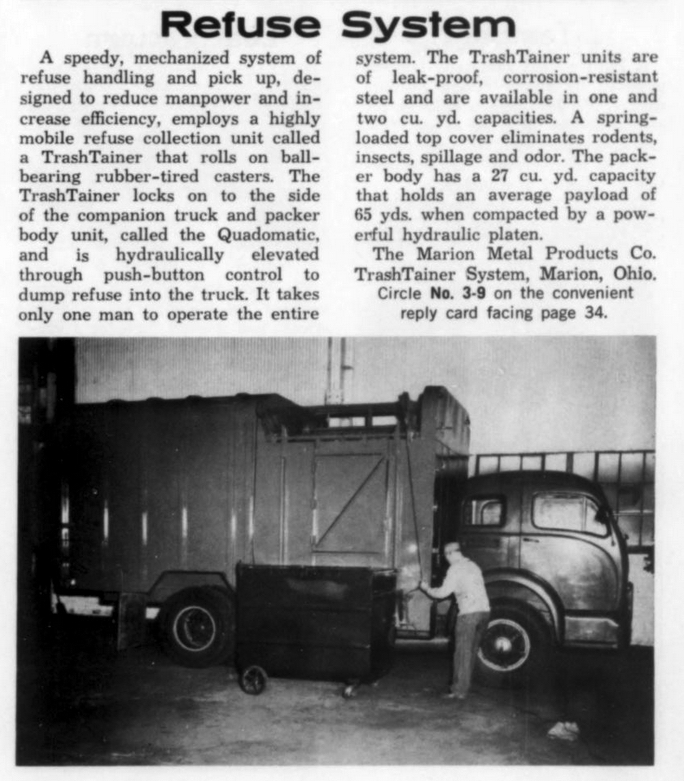

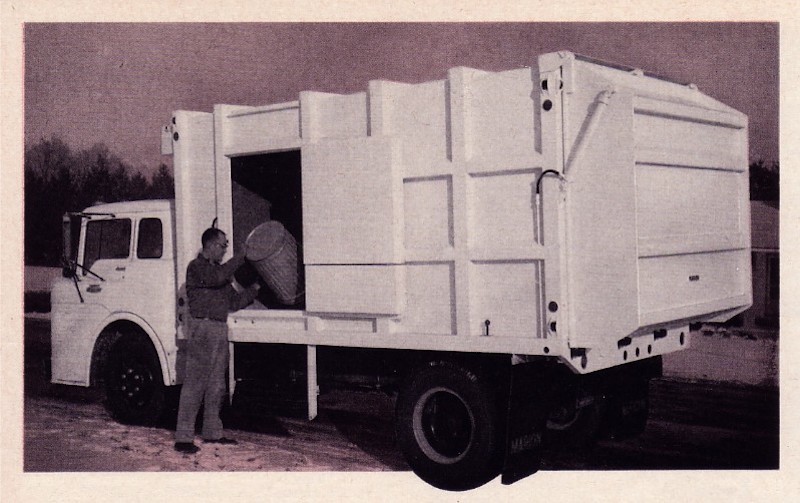

The 28-cubic yard body could be loaded from either side, handling either one or two cubic yard containers. The full-pack blade completed its cycle in 10-12 seconds, though presumably this was merely a partial sweep of the hopper area. The Trashtainer system was advertised as a commercial or residential system. In residential collection, individual containers could be left on site at housing complexes, or carried as 'fixed' buckets for hand-loading as with the old Quad-O-Matic. Side loading doors, located at either side of the body could also be used for hand loading. The packer panel doubled as the ejector, emptying the load through a top-hinged bubble-type tailgate, which was operated by a single hydraulic cylinder.

1961 Press release for the Marion Hydropaka Q. The text refers to the body as a "QuadoMatic", which was the name used when first produced by Equipment Manufacturing Inc. of Detroit. Additionally, the truck photo shown came from a 1959 Quad-o-Matic advertisement.

Trashtainer system could handle containers from either side

Hydropaka Q was a full-eject body

Hydropaka Q in New Orleans, 1962 Hydropaka 20-S

A 29-cubic yard semi-trailer Hydropaka was offered for 1963, looking like something of a cross between the 20-S and the Model Q. Production of these models continued through at least 1968, but no Marion refuse bodies were listed after that date. The declining popularity of Marion's square-loaders, once among the most advanced refuse collectors in the world, evidently spelled the end of the line for the Hydropaka.

|