Glenn Myers Non-Stop Refuse Collector

City of Tolleson, Arizona

Although now overshadowed by the concepts pioneered by Scottsdale, Arizona, their neighbors in the nearby city of Tolleson also fielded an advanced refuse collection system in the early 1970s. And not only was it automated, but featured a body and mechanism which emptied trash barrels while the vehicle was moving! The non-stop refuse collection system was the brainchild of Glenn Richard Myers of Phoenix, and was recommended to Tolleson by Marc Stragier, himself instrumental in developing Scottsdale's famous "Godzilla" automated loader. These systems blazed the trail to automation, proving the feasibility and public acceptance of radical new ways in which refuse was collected.

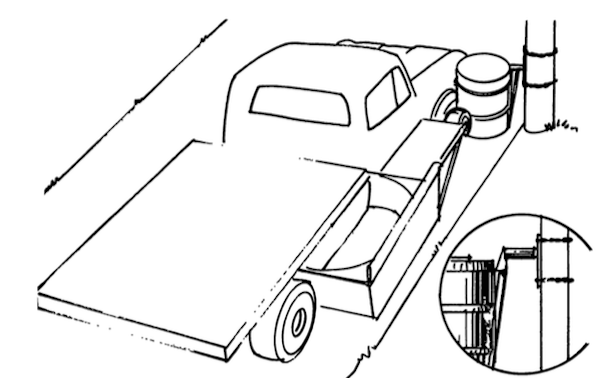

Like Scottsdale, Tolleson was seeking reduced costs, fewer injuries and more sanitary alternatives to the traditional hand-loaded collection truck. Phase I trials of the Myers system began September 9, 1970. For the first test, eight cans were pivotally mounted on existing utility poles in an alley. A pickup truck was fitted with a "mock-up" version of the concept, consisting of side-mounted trough and rubber wheels which contacted and tilted the cans, upending them over the trough as the truck passed alongside them. Once clear, the cans swung down to their original position. The test proved that the basic concept would indeed work, and the City applied for a federal grant from the EPA for the experiment. Glenn Myers set about construction of the prototype vehicle on the same chassis as used in the alley test.

Phase I test truck and can mounted to utility pole

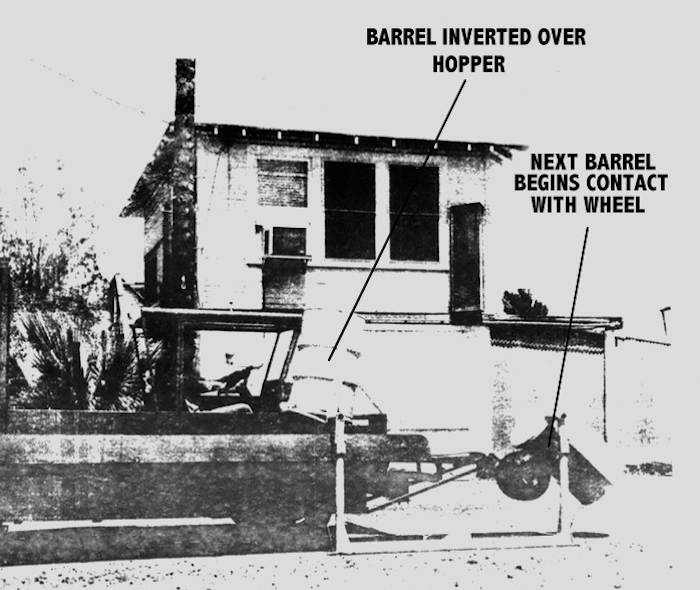

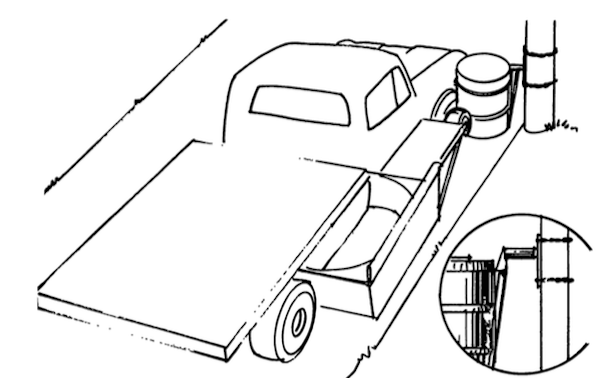

Myers fabricated a small side-load type packer (similar in design to the Hyd-Pak), with a side-mounted trough extension within which a sweeper blade was mounted. Discharge of the body was tilt-to-dump. A support frame and wheel was mounted forward of the trough, to push and upend the fixed-mount cans. The cans inverted over the trough, emptying the refuse, which was pushed from trough to hopper by the sweeper. Once in the hopper, the refuse was packed into the body in the conventional manner. 53 homes were selected for the Phase II trial, and received special cans made from 55-gallon drums suspended on posts and embedded in concrete. Problems were encountered during this phase, in that the vehicle had to be maintained at a constant speed of about 6 MPH to effectively dump the cans. Faster speeds resulted in the cans being dented by the wheel, while slower speeds caused the can to invert too slowly and become damaged by falling into the hopper.

Phase II truck (early) with rubber wheel which proved unsatisfactory

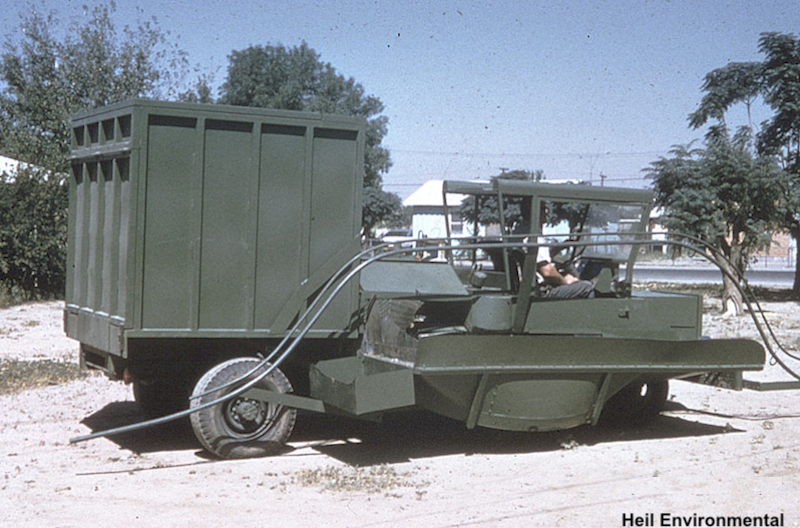

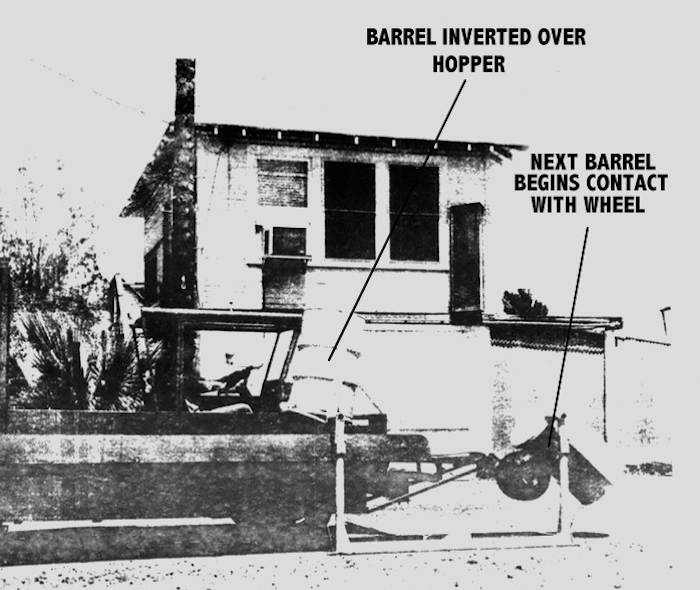

The rubber wheel arrangement was scrubbed, and Myers devised a whole new system whereby a rail was welded to the side, running the length of the vehicle, which engaged a roller sheave attached to the outside edge of the can. The driver merely lined up the rail with sheave, and as the vehicle advanced, the can was guided along the rail, inverted over the hopper and returned to the upright position as it exited the rail. It was an immediate success, and was found to be far easier for the driver, as well as allowing for variable vehicle speeds. The body and frame appear to have been extended from the first Phase II prototype at some point, and the final capacity of the Phase III vehicle was reportedly 10-cubic yards. Cardboard boxes were a problem for the sweeper blade, and residents were asked to break them down before putting them in the cans. Similarly, anything stuffed or crammed in the cans (whole boxes and brush) impeded the gravity dumping action. Bulk collection was provided periodically for those items which could not be placed in the cans.

Phase II truck with modified rail system which became standard

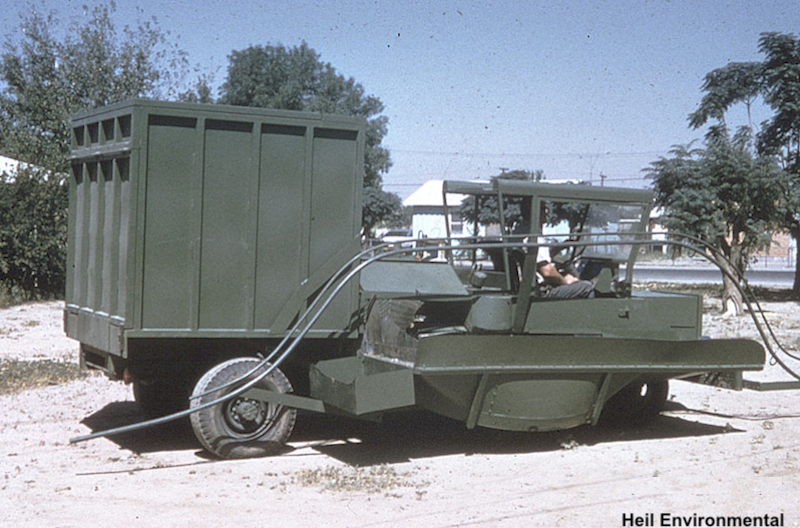

Phase III, with citywide residential implementation began in January, 1972. Tolleson's non-stop collection system garnered attention locally and nationally, including a report televised on NBC news. Myers reportedly had applied for patents, and marketed the system under the name Bionomics International Ltd. Inquiries were received from as far east as West Virginia, and as far west as Guam. However, Myers' company went out of business before any other cities could adopt the system. Tolleson remained the lone example for several years, and it was still in use as late as May 1978. Rear loaders were still used to collect 28 commercial container stops, as well as bulk refuse and brush which could not be put into the barrels. Savings were realized, even after cost of installing the posts and cans, with the collection of about 1,000 homes.

Glenn Myers went on to become a successful manufacturer and fabricator of machine tools. He was a resident of Phoenix most of his life, where he passed away at age 84 on July 11, 2015. Despite the failure of his non-stop collection method to take root, his was one of the very first successful automated systems in history. With the help of his wife May, be hand-built the collection truck, and debugged the system during its trial phases. Along with Mark Stragier, Myers is one of the founding fathers of the automation revolution.

Standard can arrangement for alleys and streets without curbing was the 55-gallon drum with hinged lid

Phase III truck with enclosed cab and air conditioning. Noticeably larger, it is likely the Phase II truck after a major modification.

Pictured here is May Myers, Glenn's wife, who helped him construct and maintain his creation

Phase III truck with three cans engaged in rail, and approaching a fourth

May Myers demonstrates the "swing-out" arm; Standard refuse can is fitted with wheels and frame and rolled to street when full.

It is hitched to post, and swung outward towards the street for collection. Momentum of passing truck swings empty can back towards house.

CAN DUMPING CYCLE

Truck approaches can which is pivotally suspended to top of post. Can has a roller sheave attached to its lower end facing the street. Posts are embedded in concrete, with cross ties to prevent twisting of the mount caused by contact with the truck.

|

Contact: the rail engages the roller sheave at the base of can, which then rises into the upwardly-curved track as the truck advances. Since top of can is pivotally connected to the fixed post, this causes the can to begin tilting.

|

Roller sheave reaches the top of the track, where it follows a horizontal path. Meanwhile, the trough is now directly below the can which has been tilted to approximately 130-degrees. Refuse falls out of can (past hinged lid) and into trough as truck continues forward.

|

Nearing the end of the trough, the can approaches the rear of the track, where it will begin its descent. A paddle blade sweeps refuse from the trough into the packer hopper behind the cab

|

Roller sheave descends rear of track, and hinged lid closes by gravity and the bottom of can pivots downward

|

Release: truck has advanced past can, roller sheave is now fully disengaged from rail, and can hangs in upright position on post. (Swing-out type posts return to "house side" by momentum as can leaves contact with rail). Up to three cans may be engaged in the rail simultaneously.

|

REFERENCES

PN-239 196 Mechanized, Non-Stop Residential Solid Waste Collection

William Da Vee, et al, City of Tolleson, Arizona

Environmental Protection Agency (1974)

Solid Wastes Management/Refuse Removal Journal, October 1980, page 70

Godzilla, Litter Pig and Trash Hog just part of history of automation by Marc Stragier

Glenn Myers obituary

The Arizona Republic, July 17, 2015

|

5/27/18 (revised 11/26/21)

© 2018

All Rights Reserved

Photos from factory brochures/advertisements except as noted

Logos shown are the trademarks of respective manufacturers

|

|